By Jeanne Russell, SA2020 Chief of Strategy

By Jeanne Russell, SA2020 Chief of Strategy

As someone wholly captivated by the power of cities to change lives, I also consume books that make that case – and especially enjoy the ones with data to back it up. Recent standouts include Triumph of the City and the Metropolitan Revolution. In the latter, a team from the Brookings Institution argues that not only do cities foster innovation, but in fact we are returning to a world of city-states. By 2050, we expect seven out of 10 people on the planet to live in urban areas.

I enjoy data, and I find the new intellectual fascination with cities affirming. Even so, I wasn’t prepared for how powerfully I’d respond to the case that cities connect to our emotions. This notion first caught my attention in a conversation with a local group determined to get San Antonio recognized as a Compassionate City. They saw the work of SA2020, with its focus on improving prosperity and education, lowering water and energy use, increasing involvement in the arts, and engaging the citizenry, as a organizing framework explained by a new level of compassion for our fellow man.

On the heels of that encounter, I read Happy City, which also offered a different take on the work we do at SA2020. We have a beautiful vision to transform our city, one that is measured in 59 indicators with specific targets such as 50 percent college completion or a 50 percent reduction in poverty. These big, optimistic goals were written together by thousands of San Antonians who believe that we are stronger together, and who feel joy when they are connected to making their city even greater.

(Cities are also jumping on the Happiness craze through dance videos… see above.)

Happy City explores the link between happy citizens and urban design. Its author, urbanist (and Canadian) Charles Montgomery, explores city building from a psychological perspective completely unfamiliar to me. His poster child is former Bogotá Mayor Enrique Peñalosa, who campaigned on a platform of making the Columbian megacity – at the time crime and drug ridden – a happier place. When elected, he aggressively returned public land that had been privatized to the public, established huge new pedestrian and bike boulevards in poor busy neighborhoods, and hired the continent’s top architects to design beautiful library parks in crowded, neglected communities.

The result was, in fact, people in Bogota did report being happier. They also became healthier, safer and and more literate. Crime fell as a result of people retaking the streets. Air quality improved as rapid transit buses and bikes replaced cars. Stress went down as people found ways to commute by walking, biking or riding buses. This was no Columbian magical thinking, as Montgomery documents similar urban redesigns reducing stress, improving health and air quality in Vancouver, New York, and Paris.

Much of his research comes from the United States, and most of it is alarming. A study of Atlanta finds that BMI (body mass index) is directly related to how close folks live to downtown, and how walkable their neighborhoods are. Another finds that men who have heart attacks are extremely likely to have recently experienced road rage. One that hit closer to home was a study of working mothers from Texas. After being asked to classify their activities for the past two weeks as if they were a series of movie scenes, they were then asked to rank them in terms of happiest and least happy… and the least happy were commuting.

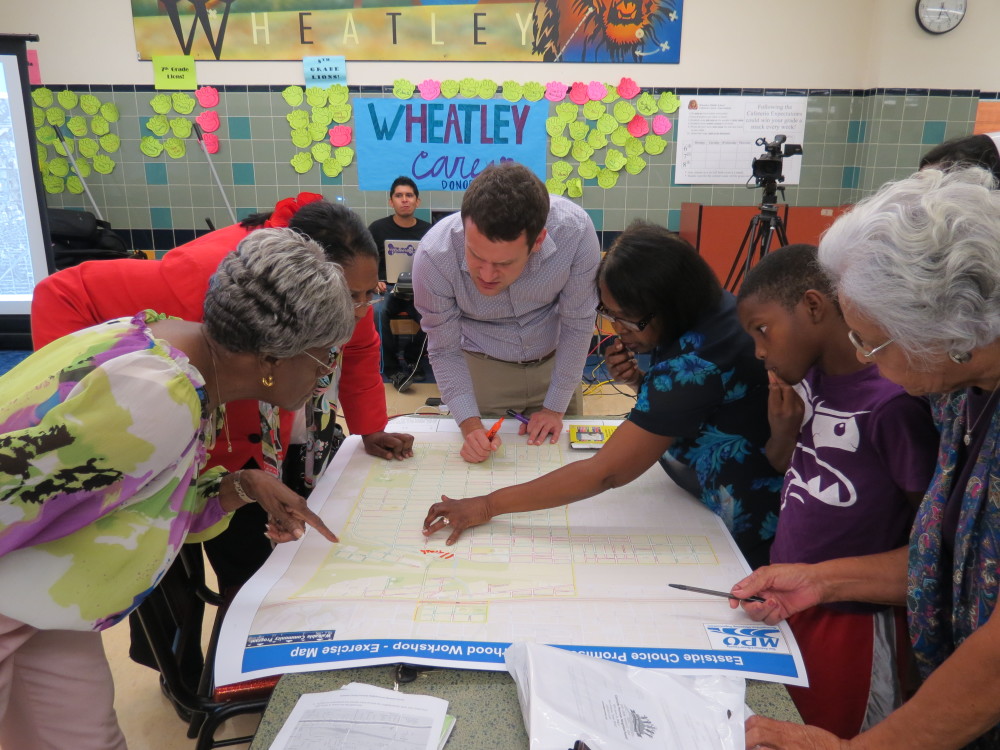

Residents of the EastPoint neighborhood at a Walkability Workshop last September, helping gather qualitative data for the City to evaluate future sidewalk and street projects to best serve the neighborhood.

Much of Montgomery’s argument is a direct attack on our car culture and an argument that when we remap our cities to allow us to spend more time walking, stress goes down and health indicators improve. He also makes a passionate case for the importance of nature in urban areas, with a series of studies that found that people were happier even when a mural of nature adorned a wall, compared to one where no evidence of green was present. Many of those points may resonate for those who heard Jeff Speck, author of The Walkable City, speak to a Centro San Antonio luncheon in January.

It’s an interesting argument to contemplate in San Antonio. As part of SA2020, people said they wanted to lower commute times, make neighborhoods more walkable, increase access to parks and green space, and decrease vehicle miles traveled (VMT). But in fact, we are making little progress on most of those indicators. In the face of that lack of progress, there are signs of hope. B-cycle has proven that there was a latent hunger for bicycling in San Antonio, especially along our linear parks. A new interest in some central city neighborhoods likely indicates a demand for walkability. National statistics show that young people are driving later – and significantly less.

Could San Antonio move more aggressively to build out a walkable infrastructure and create more public places that make people happy? For a generation who’s theme song is ‘Happy,” it seems to be a conversation worth having.